ICAN’s Global prospects reduced to regionalism

The International Commission for Air Navigation (ICAN) held twenty-nine sessions between July 1922 and October 1946, with an interruption during WWII. ICAN had developed 8 Annexes (A to H), as follows:

|

Eight Annexes to the Paris Convention |

||

|

Annex |

Name of Annex as per 1919 Convention |

Name of Annex as per Convention in 1940 |

|

A |

Marks on aircraft |

Classification of aircraft and definitions; the markings of aircraft; registration of aircraft; call signs |

|

B |

Certificates of airworthiness |

Certificates of airworthiness |

|

C |

Log books |

Log books |

|

D |

Rules as to lights and signals, rules for air traffic |

Rules as to lights and signals; rules for air traffic |

|

E |

Minimum conditions required for obtaining licenses of pilots or navigators |

Operating crew |

|

F |

International charts and aeronautical marks |

Aeronautical maps and ground signs |

|

G |

Collection and dissemination of meteorological information |

Collection and dissemination of meteorological information |

|

H |

Customs |

Customs |

With regards to Annex I – Radio Communications, this Annex had not been implemented in the Paris Convention, as the Protocol of Brussels of 1 June 1935 (signed during the 23rd Session of ICAN held in Brussels, Belgium from 27 May to 1 June 1935) dealing with this new Annex was never ratified. Work and amendments on this Annex started from 1935 without any final implementation in the Paris Convention. There was no Annex in the Paris Convention dealing with the question of Rescue.

The concept of nationality for aircraft was adapted from maritime law where the national flag is used to indicate a ship’s country of registration. The issues of aircraft nationality and registration were considered during the International Air Navigation Conference held in Paris in 1910. Despite the absence of a final signed agreement at the end of that Conference, the principles of the nationality of aircraft and its registration were formally incorporated into the Paris Convention. Chapter II – Nationality of Aircraft and Annex A to the Paris Convention describe the rules and specifications for aircraft nationality and registration.

For reference, the full text (in French) of the 1919 Convention and its 8 Annexes were printed in a booklet of 66 pages, 13x21½cm pages. The standards in aviation grew over the years and, in February 1940, the trilingual text (in French, English and Italian) of Convention with its Annexes was held on 156 letter-size pages.

|

|

|

ICAN’s Premises Avenue d'Iéna |

To assist the Commission, it was agreed to establish a small permanent Secretariat under the direction of a Secretary General. As architect of the International Air Convention of 1919, Mr. Albert Roper from France was naturally elected to this position during the first ICAN Session. ICAN was located in Paris (provisionally at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs: 3, rue François 1er; from January 1923: at 20, avenue Kléber; from the first half of 1932: 15 bis, rue Georges-Bizet; and later from May 1937: at 60 bis, avenue d'Iéna), where it remained throughout its existence. In fact, the European Office of ICAO in Paris, on its foundation, took over the offices of the ICAN Secretariat and remained there for its first 19 years until August 1965.

The technical work of the Commission was developed by its 7 sub-commissions and 2 committees of Experts (in effect in 1940), which met at regular intervals:

1. Operational Sub-commission;

2. Legal Sub-commission;

3. Wireless Sub-commission (in French, this sub-commission was named: Sous-commission de T.S.F., transmission sans fil or télégraphie sans fil);

4. Meteorological Sub-commission;

5. Medical Sub-commission;

6. Maps Sub-commission;

7. Materials Committee; this Committee became later a Sub-Commission;

8. Committee of Experts on Customs;

9. Committee on Standardization (added by mid-1930).

Over the years, Special Committees were created, such a Special Committee for the revision of the texts of the Annexes to the Convention, an Audit Committee, a Special Committee for the study of the grading of altimeters, a Special Committee for the study of the regulation of air traffic in bad visibility, etc. The Commission met initially three times, then twice, and from 1930 on once a year.

Although finely crafted, the International Air Convention also contained some articles that were to become quickly controversial. First of all, Article 5 provided the right to a Contracting States to not permit the flight above its territory of an aircraft that did not possess the nationality of a Contracting State. Moreover, Article 34 of the Convention did not grant equal voting rights to its members, enshrining thus a permanent status of inequality among States who could become parties to the Convention. Amendments to these two articles were to enter into force after the States had declined to become parties to it. A modification of the latter article entered into force in May 1933: each Contracting State had, starting from this date, only one voting right.

President Wilson of the USA played a leading role in the establishment of the League of Nations; the idea of his plan was to settle problems between nations peacefully. Wilson tried to persuade the international community that the league would discourage aggression and tackle the underlying problems that often lead to war, such as poverty. The creation of the League was a predominantly British and American affair. Yet Wilson was unable to convince Americans to commit themselves to membership in the new organization. Mainly America had suffered civilian casualties in WWI and many people in the USA wanted to keep America out of European affairs. Also joining the League meant that this might involve having to do things that might set back the economy or damage America otherwise. Finally, there was also the fact that America had had little involvement in the war and had some civilians (especially German immigrants) who had little or no support for British or French policies and/or the Treaty of Versailles. The fact that the CINA was considered to be formally linked with the League of Nations was one of the reasons why the USA did not joint it and did not adhere to the Paris Convention of 1919. Moreover, the Paris Convention was rejected also by the states of America, because it retained the thesis of state sovereignty over its airspace; the latter states preferred the Havana Convention of 1928 providing for freedom of commercial communications.

Russia (closed to international air traffic) was never represented at the Paris Peace Conference and showed no interest in becoming a member of ICAN. China was closed to international traffic too. Those countries and others (Germany on the verge of joining in 1939, Mexico and Brazil) had not adhered to the Paris Convention while they applied most of its guiding principles.

|

|

|

Belgium – Brussels 1935 International Exhibition |

With thirty-seven States having ratified its Convention in 1940, ICAN had been a real success, at least within Western Europe. It shall be noted that, before WWII, the world consisted of approximately fifty sovereign countries; moreover, at that time, it was not absolutely required to have agreements covering the whole world, as the airlines usually did not fly beyond continents, except for some airmail flights to South-Atlantic and for some transatlantic flights which started in 1939.

|

|

Brussels 1935 - International ExhibitionPoster stamp showing the Heysel Palace 5 |

The Paris Convention was superseded by the Convention on International Civil Aviation signed at Chicago on 7 November 1944.

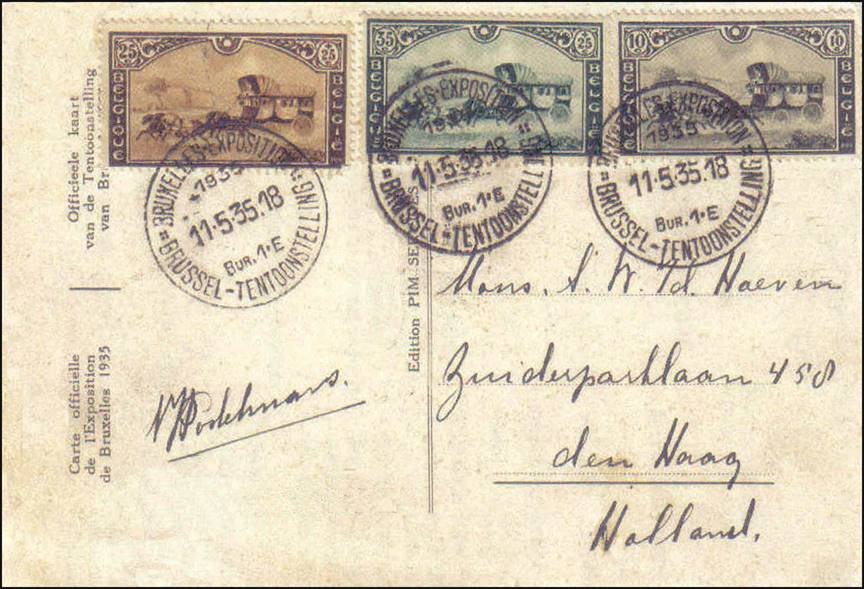

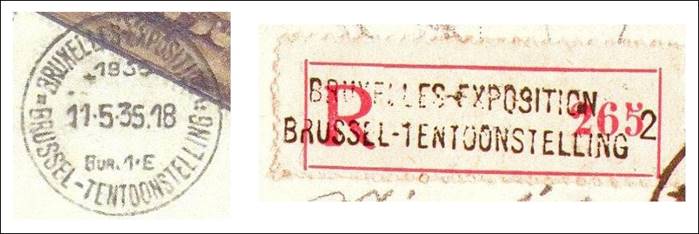

The 23rd Session of ICAN was held in Brussels, Belgium from 27 May to 1 June 1935 in the framework of the Brussels World Fair. The mail with a rectangular hand-cancel for the Session, dispatched for the participants, was obliterated at the postal office of the exhibition. This seems to be the only known postal item related to ICAN.

ICAN prepared an Official Bulletin regularly published to report on its activities, whereas Albert Roper edited the Revue Aéronautique Internationale in his personal capacity (outside his functions of ICAN Secretary General).

From 1922 to 1939, ICAN held 27 Sessions. The first Session was held in Paris from 11 to 13 July and on 28 July 1922. At the pace of two or three Sessions per year until 1929, ICAN met only once a year from 1930. The Secretariat was the only permanent body of the Organization and counted 28 staff in 1939.

When the International Convention for Air Navigation (ICAN) entered into force in 1922, it was quickly realized that the ICAN could not resolve the multiple questions of details existing only in a few countries. Some sort of regional organization was created through international aeronautical conferences for a group of countries in a region. These conferences were established to address multiple problems posed by the day-to-day operation of airlines flying between the various countries of the region, e.g. radio-communications, weather forecasts, organization of air routes, use of aerodromes, operation of lights, standardization of aircraft parts, test of night services, etc. Three of such conferences existed during the lifetime of the ICAN: the International Aviation Conferences (which periodically gathered aviation representatives of a group of states of Western and Central Europe), the Mediterranean Aeronautical Conference (aimed at exploring the problems posed by airlines operating in the Western Mediterranean Sea), and the Aeronautical Conference of the Baltic States and the Balkans (established for countries of Eastern Europe). More information on these Regional Aeronautical Conferences can be found by clicking on the following link: International Aviation Organizations Working Alongside ICAN And Dealing Exclusively with Aeronautical Matters. No central secretariat existed for these conferences. In each delegation, a delegate was appointed as secretary for his country and was responsible for centralizing all communications relating to the conference. The secretary in the country, where a session was held, provided the secretariat for this session from the drafting of the agenda until the drafting of the final report. Albert Roper attended these conferences as Provisional Secretary of the ICAN (until 1922) or Secretary General of the ICAN (from 1922). In fact, the ICAN itself was in some respects a regional organization.

The twelve draft Technical Annexes adopted at the Chicago Conference in 1944 expanded the regulations adopted by ICAN before the war and contained new provisions dictated by the experience in air navigation gained during WWII. ICAN remained inactive during five years due to WWII and these few years of interruption in the work resulted in extremely large amounts of material brought for discussion. Moreover, as the Paris Convention and ICAN were to remain in existence until the coming into force of the Chicago Convention, it was important to fill the gap which constituted a lack of up-to-date technical regulations in relation to air navigation in the interim period, i.e. before the final Convention would become valid.

The ICAN Secretary General took the initiative, immediately after the Chicago Conference, to convene the ICAN Sub-Commissions and technical Committees to conduct the review of the Annexes to the Chicago Convention and to consider the amendments required to the Annexes to the Convention of Paris; these meetings were held at the ICAN headquarters in Paris between 9 April and 5 May 1945. With similar intention, ICAN adopted a new text for the regulations for the International Radio-electric Service of Aircraft and for the instructions concerning the International Aeronautical Telecommunication Service. The recommendations of these meetings were submitted first for advice to the ICAN Legal Committee which met between 12 and 16 June 1945, then to the 28th Session of ICAN, held in London from 21 to 25 August 1945, which adopted a large number of these changes for inclusion in its Annexes. The purpose of this work was to attempt to bring the Technical Annexes of the Paris Convention in line with the Technical Annexes drafted at Chicago, so as to ensure an eventual smooth changeover, when the Chicago Convention would come into force.

The Interim Council of the Provisional International Civil Aviation Organization (PICAO) met in Montreal on 15 August 1945, and offered the post of Secretary General to Albert Roper, who was later authorized by ICAN to occupy the same function within ICAN until its liquidation. During its 29th Session (final Session), held in Dublin, Ireland from 28 to 30 October 1946, ICAN adopted the resolutions for its future liquidation, which came into force on 7 April 1947, date of entry into force of the Chicago Convention. ICAN’s Committee of Dissolution, created at the 29th Session, managed the dissolution. On 31 December 1947, all ICAN’s operations were closed down; its assets were transferred to ICAO and part of its staff was transferred to ICAO’s European-Mediterranean Office in Paris.

|

|

|

Opening meeting of ICAN first Session held at Quai d’Orsay, Paris, France on 11 July 1922. Albert Roper is standing somewhat in the middle on the second row.

|

|

|

|

Visit by the ICAN Delegates to Japan (1930). Albert Roper is on the left-side.

|

|

|

|

Machine cancel and registry label (upper), Hand cancel (lower) from Anvers International Exhibition, where the ICAO’s 18th Session was held from 24 to 27 June 1930. The Exposition was held from 3 May to 3 November 1930.

|

|

|

|

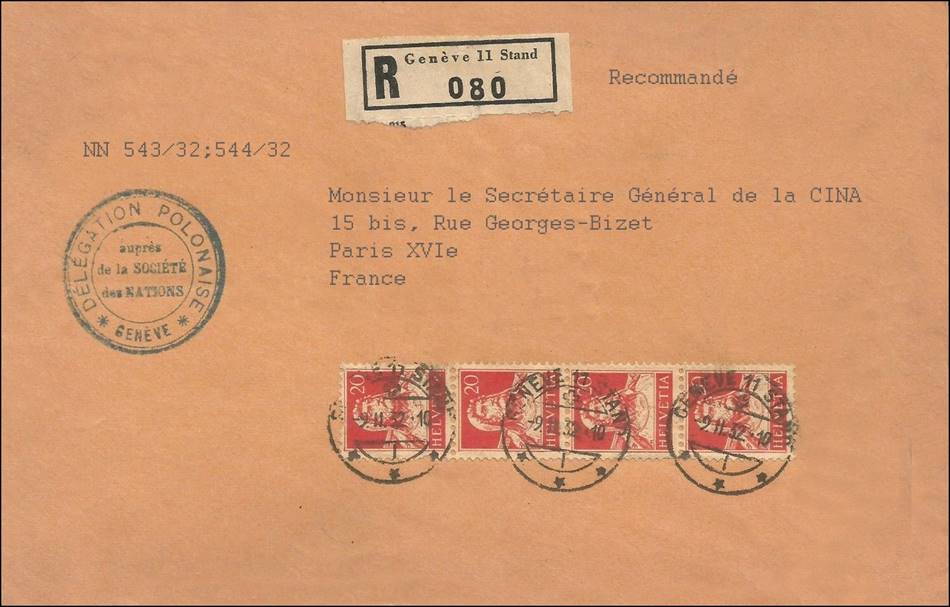

Polish Delegation to the League of Nations registered cover sent to ICAN Secretary General. Postmark dated 9 November 1932.

|

|

|

Belgium – Brussels 1935 International ExhibitionPostcard with cancel of the exposition (11 May 1935)

|

|

|

Hand cancel and registry label used at the Universal Expositionheld in Brussels, Belgium (where the 23rd Session of ICAN was held)from 27 April to 6 November 1935, |

_________________________